“Perhaps we are born knowing the tales, for our grandmothers and all their ancestral kin continually run about in our blood repeating them endlessly, and the shock they give us when we first hear them is not of surprise but of recognition. Things long unknowingly known have suddenly been remembered. Later, like streams, they run underground. For a while they disappear and we lose them. We are busy, instead, with our personal myth in which the real is turned to dream and the dream becomes the real. Sifting this is a long process. It may perhaps take a lifetime and the few who come around to the tales again are those who are in luck.” P. L. Travers

The other day I came across a study from a group of anthropologists at Durham University in the United Kingdom, who compiled 275 of the most famous fairytales to trace their origins i.e. to find out, how old are fairytales anyway? To do this grand task wondered by many others before them, they followed the genealogical branches of language. Different cultures and languages shared the same stories, so what they did is basically trace back to where was the shared language from which it all began; where was the root? Who was their last common ancestor? The study found that the oldest fairy tales still in circulation today are between 2500 and 6000 years old.

Here is what stuck with me though: story and language go together, hand in hand. At the heart of language are the stories and traditions. Whatever words linguists wrote at the beginning of time, was all to create the background of the stories, so that language can develop. Tales are not just the hands that hold us but the very stories we tell ourselves to shape our own realities, and comfort our worlds. This is what we do each day with words and thoughts, also.

Stories lean on stories, just as cultures lean on cultures. And folklore is a way of looking into another culture from the inside out; just as we look into ourselves. Fairytales and lore are wisdoms passed down to us through generations. And while the original tales were actually written for adults (more on that below), it is important to continue to tell fairytales to our children. Because otherwise, we deny them of roots and the cultural, historical heritage. Children today face a serious problem: starvation of words, language and imagination. Just as stories depend on stories, so does words on words, and lives on lives. Connection and continuity are the natural, most essential links not just of cultures, but also, of our ever longing hearts.

The Beginning.

In poetic style similar to ancient mysticism, fairytales are just symbolic allegories built on the theme of the soul’s path towards self-discovery and unity. The well known tales of The Sleeping Beauty, Snow White and Cinderella, are based on folklore and we’ll find many versions of them throughout the world, throughout many cultures. Such tales carry the same symbolism – and are based on ancient wisdom and esoteric knowledge. Before there was time and language – there were symbols – and this is how our ancestors, including philosophers and alchemists, shared knowledge.

Like the web of wyrd – everything in our world is connected but translated into its own language resonant of the land and people. In fact, if we dig in deeper – we’ll find that all mysticism, religion, philosophy and science is connected; we’ll find that no matter what field of belief we follow, we’ll be led to the same understanding.

Fairytales carry this deep symbolic language – one of the drumming of the human heart and imaginative theatre of the mind – as they reach the inside corners of our psyche (if we allow them) to make sense of what was maybe unknown and unseen, as we recognize parts of us outside of us.

Fairytales remind us of the important primordial widoms of life passed down to us from our ancestors – if only we have the eyes to see.

Elemental fears, sexual taboos, strong desires and subconscious urges are all at the core of fairytales. They articulate concepts that are emotionally difficult or culturally unacceptable to voice.

Every age has its monsters, whether witches, vampires, terrorists, viruses, corrupt governments and every age needs to have a glimpse of hope that perhaps we as human beings have the ability to defeat these monsters and injustices, and be kissed by love once again. Every age has its magic too. It is precisely tales that speak to the irrational mind, to the subconscious. Fairytales are nearer to poetry and mysticism, in the way that they go into the hidden corners of our psyche, where our own magical powers can be uncovered. These unspoken languages conjure up whole new worlds of understanding and living, and of greater awareness through symbolism and mythic archetypes.

This is where the true language of fairytales is found: in our willingness to break the limitations of words, remembering the context of the time when they were written, while opening our perceptions to see their true essence in the wisdom that the story holds. Otherwise we miss so much of life.

The Original Fairytales.

The original fairytales were actually written for adults, and this why they are quite disturbing with dark, sexual, violent images reflecting the human condition at the time when they were written.

The term “fairytale” which is now used by the English speaking world as a generic label for magical children’s stories, was actually started by the literary salons of 17thcentury Paris by a group of writers and wrote and published tales for adult readers. The tales had their roots in the oral folk traditions and upon much popularity, they were later on adapted for children.

Folk tales have been a part of storytelling tradition since the beginning of time; way before people even knew how to write the stories, they were telling them. This is how they passed on wisdoms and educated themselves. The tales included magical elements such as enchanted forests, witches, fairies and sorcerers, and were humbler stories than ancient mythology, heroic romances and higher philosophy texts, which made them relatable and reachable by people of the lower classes, such as women, peasants and all outcast groups. Although we find magical elements in medieval literature, it is 16thcentury Italy where the fairytale became a genre of its own with the publications of Giovan Francesco Straparola’s “Le piacevoli notti (The pleasant nights, 1550-53)” and Giambattista Basile’s “Lo cunti de li cunti (The story of stories, 1534-36). Both authors acknowledged that their stories came from old folk and women storytellers, and preserved the oral folk tradition while using their educated sensibility and language, to make them into literary works. Between them were written some of the earliest classic tales of Rapunzel, Sleeping Beauty, Cinderella, Beauty and the Beast, Little Red Riding Hood, Snow White and Puss in Boots. The tales were meant for adults and as such included elements of sensuality and darkness that were never meant for children’s innocent ears. Upon their popularity they were retold and adapted for children, by Brothers Grimm in Germany and Charles Perrault in France in his Mother Goose Stories.

The Italian tales influenced many generations of writers in Paris. Prior to the 17thcentury, French folk tales were considered the vulgar stories of peasantry. Some of the middle class knew of the tales because they were passed onto the family by the nannies and servants, and yet they were frowned upon and often told and admired in secret. Around the middle of the 17thcentury, the Italian tales emerged in the salons of Paris. The salons were gatherings hosted by prominent aristocratic women, where they discussed important issues of the day such as social issues of marriage, financial and physical independence, love, health and access to education. These were times of oppression and suppression, where divorce was unheard of, abuse was a daily reality, childbirth death was common, education was not given to most women and arranged marriages were the norm. Some of the most gifted women writers came to these salons, one of which was Charlotte-Rose de La Force, who borrowed elements from the original Rapunzel (Petrosinella) written by Basile sixty years prior, and wrote her retold version, called Persinette, publishing it in her fairytale collection Les contes des contes in 1697. La Force was part of the group of writers who created adult fairytales in the literary salons of Paris, including the other writers, Charles Perrault, Madame D’Aulnoy and Madame de Murat.

Many people might see Rapunzel as some tale about a weak girl who plays a victim locked in a tower, waiting to be saved – and as such disempowering or in other words, a horrific narrative considered by neo-feminist groups. But here is the thing: The tale of Rapunzel, told by both Basile and La Force, is actually very empowering telling the story of a young girl who was not weak at all. La Force, who was known as a very rebellious woman, wrote just like Basile, for an educated, aristocratic audience, that were meant to both entertain and bring awareness to contemporary life. One of the issues of that period was the common practice of arranged marriages, where daughters were used to cement alliances and settle debts; they were sold off. Sex was the husband’s legal right, whether or not the woman wanted it, consent was a mirage and rape was reality. And the disobedient daughters and women, were sent away in convents or locked up in madhouses. It is no wonder then, that French tales are filled with stories about girls handed off to wicked witches and creatures, by their cruel parents, or locked up in towers where only true love can save them.

La Force and other writers, fought hard to champion the idea of consensual marriages ruled by love and humanness. The emphasis on the themes of love and romance may seem silly today, but these stories were progressive, rebellious, meaningful and greatly important for their times. La Force herself was an independent thinker who came from a noble family and caused several scandals because she chose to live a life that was authentic and true to her heart. She fell in love with a man much younger than herself and attempted to marry him without parental permission. His family locked him away to prevent the marriage, and she snuck into his room dressed as a bear with a travelling theatre troupe. They escaped and married, until the law caught up to them and annulled the marriage. La Force then published satirical works criticizing King Louis XIV and when she got caught, was exiled to a convent to pay for the crime. Actually this is where she wrote her book of fairytales. Rapunzel, or Persinette, is a sensual story with sly humour at its core. Rapunzel is a strong character, who showed herself to be quite resourceful when it came down to it and had the courage to run away following her awakened in desire heart. She even became a single mother (because the dude got dropped into some thorns, lost his sight and got lost) and looked after her children for a few years in some remote unknown place, faced with many hardships. After the two lovers reunited, Gothel sent them famine and all other imaginary evil events, but they persevered, staying strong together. Humbled by their true love, Gothel’s heart finally showed signs of humanity and she sent them well on their way. Towards the prince’s castel of course. I can only imagine Gothel lived a better, happier life after, since she decided to let go of the bitterness in her soul.

This is just one story. There are many more. Thousands of years worth more, holding not just the story but also, the very hands of the writers’ lives. The history of fairytales is too vast for a simple article like mine. But may this be just an eye opening, for curiosity to arise. I do hope that we can all inspire the new generations with the bravery and morality that La Force, Basile and all others inspired for us.

I recently came across some interview by a woman, a professor of anthropology holding a glamorous PhD who talked about how Scheherazade is a role model for women, because “unlike the Western fairytale and folklore characters like Cinderella, Scheherazade is not waiting for some prince to “save her.” It is really, really hard for me to hold my tongue and not react to this ignorance, especially by someone who has high education and is in a capacity of teaching other people, spreading her ignorance and not-well-researched information to others. It’s hard for me not to react because ignorance is a choice. And our ignorance then becomes our own imprisonment and limitation to intellect, which then becomes plain stupidity spreading around like a virus.

If this professor actually did her research, then she would know that Cinderella is a story about a girl who was neither weak nor simple by any means; and that she never ever waited for a prince to “save her”. Cinderella, while Disney-washed in modern times, was a girl who stood strong in her authenticity and hard work, and despite the envious environment by other women and the hardships and abuse that she was faced with, she remained true to her inner self. If anything – the original story of Cinderella teaches us about some real brave qualities that are truly empowering. You can read my analysis about Cinderella, here.

What I don’t understand is why do people feel the need to devalue something or someone else, just to make themselves or their point more relevant or valuable? Scheherazade is a beautiful character and I adore her, since I grew up with 1001 Nights and still have its complete works on my shelf. She holds her own wisdoms, and so does Cinderella and all others. Why do we even have to compare these two to begin with? They are completely different. This is the problem with modern society and even the so-called feminism; empowerment does not mean disempowering others, so that we feel better about ourselves, just like feminism isn’t about emasculation or devaluing other women who don’t fit our own narratives.

Intelligence means that we are considering other viewpoints that challenge our own beliefs and narratives, and are willing to admit our biases, and change upon new informational intake, when we are wrong. This is what growth is. This is what spiritual development is; our willingness to open our perceptions so that we expand our consciousness. Familiarity breeds familiarity. And repeating the same old crap, becomes our very own behavioural pattern and limitation in life. Learn the history, research the facts, before making ignorant statements. Because ignorance is a choice and there is no excuse for our own laziness in putting in some effort.

What turns me off about modern retellings, is that they wash-out the original narrative and the essence of the characters, while saying that these are the real, old stories. But they are not. Too many fundamentals have been changed to make these claims and in ways that lessen the stories’ classic themes. For example, in Disney’s 2017 Beauty and the Beast film, the father is presented as harmless and his role in Beauty’s imprisonment has been greatly diminished by a mere accident of circumstance. And Beauty’s jealous sisters have been deleted. And the entire family conflict has been deleted. There is some arrogant suitor, Gaston, added as a presentation of a simple one-sided villain. In short, the characters are plain, simple, unambiguous, boring – and don’t go through any growth or development of character. There is no depth. In the old tale, Beauty makes mistakes but she learns from them. And so does the Beast, who reflects on his own incredibly selfish, cruel and aggressive nature, to make an effort to change into a better man – and only then does Beauty see the humanness in his eyes and falls in love. They go through their unique maturations and we see depth in their characters.

Just like Cinderella. The old tale shows her feisty, active and witty nature – while Disney, and the PhD professor that I mentioned above, portray her as some helpless, pitiful, useless heroine who has to be “saved by a prince” while spending her days talking to mice and birds, as if completely delusional, until a magical pumpkin takes her from rags to riches.

There is nothing wrong with adjusting and changing stories and retelling them – that’s fine – but we need to be transparent about it and remember where we came from. As for us as people, we need to stop being so ignorant and plain stupid, recycling wrong things. Remembering the history of these tales and the times when they were written is important – because when we deny or forget history, we are more likely to repeat it. War, oppression, suppression, abuse, genocide, famine – people locked in towers, not just metaphorically but also, literally – these were a reality. And we must remember it, so that we remember wisdoms they taught us. Otherwise, by erasing history we are only destined to repeat it.

It literally pains me when someone diminishes the importance of tales into some two-dimensional simple narrative and I want to scream about it in frustration. People’s ignorance annoys me to the point of physical pain – because they choose to be that way. Because we miss so much from life. We miss heritage, richness and deep wisdom, that was meant for adults to begin with. And we don’t grow. And we don’t develop. And we don’t mature. And it is 2020 but we are repeating the same mistakes all over again. Because we choose to forget and we choose to remain ignorant.

As the Natives say, our greatest adversary to self-development, reclaiming our power, and ourselves, is forgetfulness; forgetting our hearts, truth and ability to love.

I don’t see our past as something horrible teaching us “lessons” because that would imply some crime and punishment mentality, nor do I see our past as something separate from us as if it’s a big bad stepmother. I see life as a continuous stream of consciousness, as little stories with their precious wisdoms for that moment in time, as if we sat on a bench and opened up a book to read, or write the pages ourselves. On that bench, we’ll sit with it, sometimes long because we need to think it through (maybe it is in another language or we are just trying to figure out the links of the characters) or sometimes we’ll immediately close the book because we’ll remember what happens when we go into the witch’s candy house. And then we’ll stand up and continue walking until the next bench; no better, no worse, just different in its uniqueness. This is how I see our lives; a bunch of benches and potential wisdoms. It is our choice what we get out of these books and stories, whether written by us or not.

Sometimes people say, forget the past, forget the old. But it’s almost like we have to force ourselves out of the old and into the new and why should we anyway? I don’t think we are capable of that, and in fact, we create even more tension just by forcing ourselves to think that way; life is about discerning, not forgetting. It’s about marrying the old with the new, to create something else of heart, love and authenticity.

Storytelling preserves our generations and family history. Most people don’t know much about their own family trees and we just forget to ask, or to share the stories. And we lose generations of stories and all the benefits that come with them. Our families are the most important groups that we belong to and identity with; they remind us where we came from, and provide models of both good and bad, so that we make more aware decisions in the future. Moreover, storytelling closes the generational gaps and we become more appreciative and understanding towards one another.

Let’s Think of Children.

It is no easy task being a child. Real childhood, as opposed to our fantasies or denials, or because of pure forgetfulness, is full of adversaries, worries, unknowns and some intense moments, for many even traumatic. In every step of the way, they are faced with the harsh realities of their larger than life dreams as they come crashing down. And they face the mysterious adult hands of “No” which would remain mysterious for reasons they are incapable of understanding yet.

Do you remember how you felt the world through your childhood eyes?

No matter how much we shield or protect our children as parents, childhood always has its own intensities and fragilities. Here is where the wisdom of folk and fairytales comes, which we too have forgotten: Hope is often the through-line of the narrative but the teaching isn’t that it’s easy. Hope is a struggle. Hope is dangerous and challenging. And hope is absolutely needed. Because now more than ever, we need to try really hard to meet the world with hope. The older we grow, the harder it becomes and we need to remember.

But considering the fact that fairytales can be quite dark and even frightening, should we continue to tell them to our little ones?

I think it’s important that we do and perhaps even more important today than ever before should these tales be told and repeated again and again.

The violence or darkness within them is always contained within a reasonable and satisfying structure; both good and bad are separated, and there are no grey areas. To a child, this is actually important from a psychological perspective because unlike adults, a child until the age of seven only has its emotional body forming, not yet its mental body. The appearance of villains and evil people actually allows the child to freely, and safely, project its own violent feelings onto these separated character beings. Since children are unable to express their anger, sadness and even hatred directly towards adults (because they depend on them), the children can therefore displace these natural emotions and aggressions as personified by the tales’ villains.

Simultaneously, since their emotions are expressed in a satisfying manner, children can then identify with the good characters. They have now won against the dragon and the witch, escaped through the thorns of the scary forest, and can rescue the princess or acquire their justice after their hardships. Children can also identify with the weak and tiny, who are able to overcome all odds and still triumph, like the little mouse, rabbit or the poor shoemaker. Because like I already talked about; the go-through narrative of all tales is hope. And it is hope and fear, that ultimately guide our decisions in life. It’s a choice we make each day, and meeting the world with hope is of much importance. Tales remind children of that, and it’s a wisdom deeply ingrained within their psyche. Tales permit both the expression of our natural humanly aggressions while preserving the essentials of life: hope.

We have to remember that children are fragile, helpless and completely dependent. And in these ancient tales, they find a comforting hand, holding them through it all. Especially in the times when their worlds are confused and they don’t know how to make sense of it, and don’t even know the questions to ask us, it is tales that speak to them in languages, that while we as adults may have forgotten, they always understand and feel. Children need these tales, because they crave for intimate connections offered by the spirit world, to which they are still very connected intuitively. And we as need these tales as well – because they remind us of our roots, of where we came from because we are in desperate need to remember who we were.

In an age where everything is increasingly dehumanized, as people are turned into non-people soon to be robots, just faces on a screen, swipeable and disposable, and where even culture and art seem to diminish our lives as opposed to enrich it, it is precisely tales that offer a much needed link to the values of humanity and humaneness. When I was a little girl, every time I’d listen to a tale, I’d have to use my imagination. I’d have to first believe it, to then see it. This is one of the greatest gifts of our psyche’s development: our imagination, rather than purely visual instant gratification/stimulation that we get from TV or media. In fact, it is imagination that makes the best and most innovative change-makers and problem-solvers in the world. We need to have the humility to accept reality for what it is, and the audacity to imagine it otherwise.

Children’s tales also offer the perspective, or rather alternative, that there are some other magical lands into which we can delve, outside of the malls or corporations. They inspire the immesurable qualities of imagination, questioning, instinct and even rebellion. And as far as I am concerned, these are good qualities leading to independent, forward thinking.

Fairytales are the first teachers to children, as were the first teachers of all humanity, secretly living on continuously in the story. For these are not just stories heard, but stories we went into; we lived in them and the characters, we struggled with them, we sharpened our instincts in the woods and learned perseverance through hardships and failures. Our ever after had to be earned because not everyone got to it.

Most fairytales aren’t about heroes with special powers. They are about humble, ordinary people or tiny animal creatures, who are not even the most beautiful, talented, bravest or strongest. And even when they are, these qualities are often hidden under ash or donkeyskins, because they are unnoticed, unseen, unheard and unappreciated by those around them. Any gifts that they are given, and often over-dued, are because of their virtues such as kindness, and devoted work behind the scenes. And yet even the beautiful ones, like the princes and princesses also go through hardships and hurdles; and we learn that we all share things in common. The characters in tales get cheated, beaten, bullied, robbed, but they learn that they are stronger than they thought. And we, as them, learn to cope with life, also. Not all of them got their happy ends, especially if we’ve read Hans Christian Andersen or many of the Swedish tales. And yet we remember that it is our own feet and hands that shape and weave, and we can take another step, and then another, and maybe things will work out. Because you just never know who might show up in the story, on the next line, or page; maybe kindness from a hand of a stranger or a firepit in the cold woods.

The lessons from tales are subtle but will stay in the subconscious mind, through adulthood; because these are the moral and humane structures and foundations of the life that we build for ourselves.

And we learn to persevere.

And we learn to trust.

And some learn to love.

Thankful we must all be to our ancient tales, for they are words repeated many times over many thousands of years, soothing us, nurturing our imagination and relieving our fears. They hold our hands in ways we couldn’t even imagine; and whisper to us in their tiny, frail yet very convincing voices from the forgotten doors somewhere in the back of our minds: We can only love what we appreciate.

So, lay into my lap, and let me tell you a real tale; one as ancient as time.

With love,

Lubomira

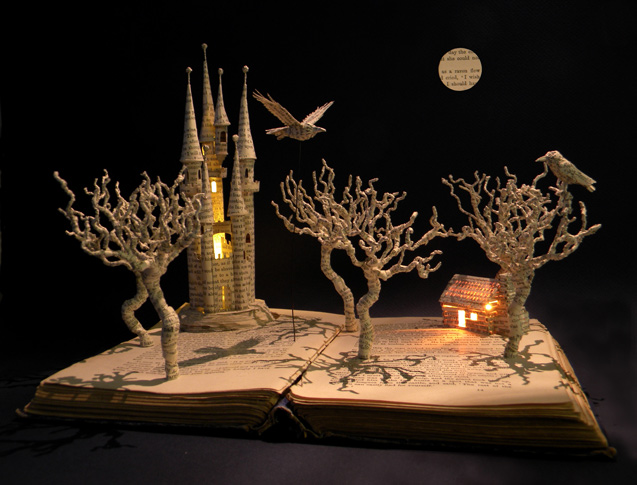

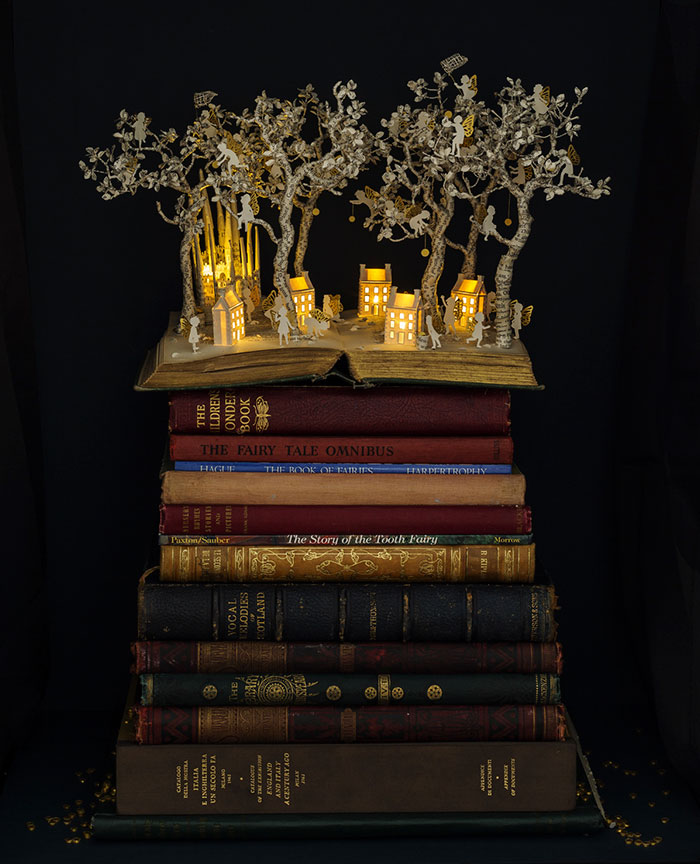

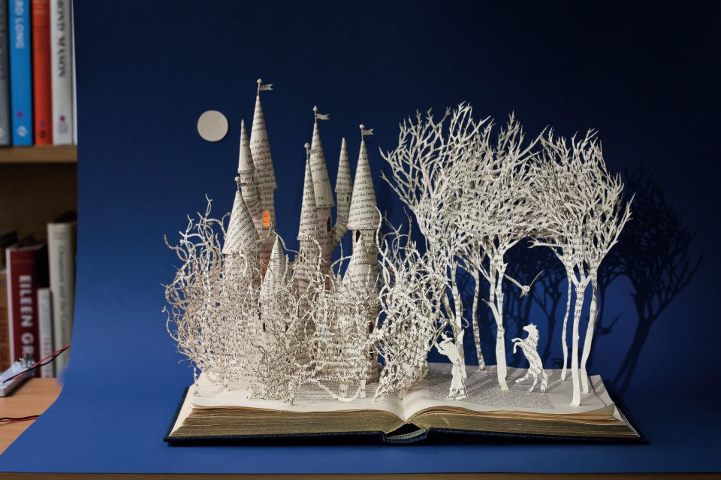

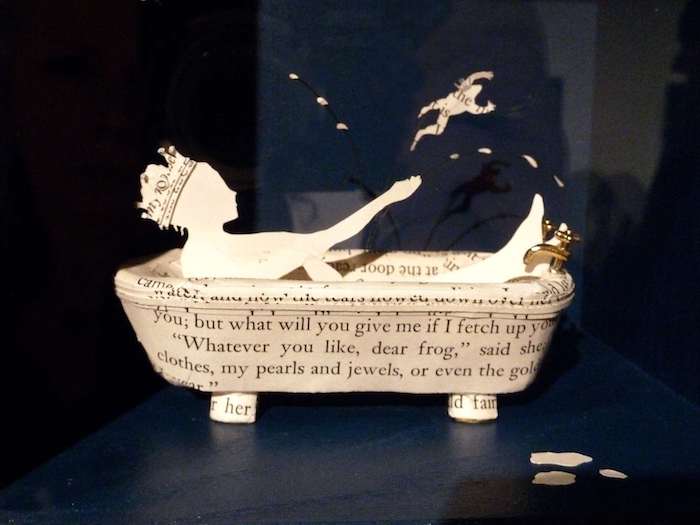

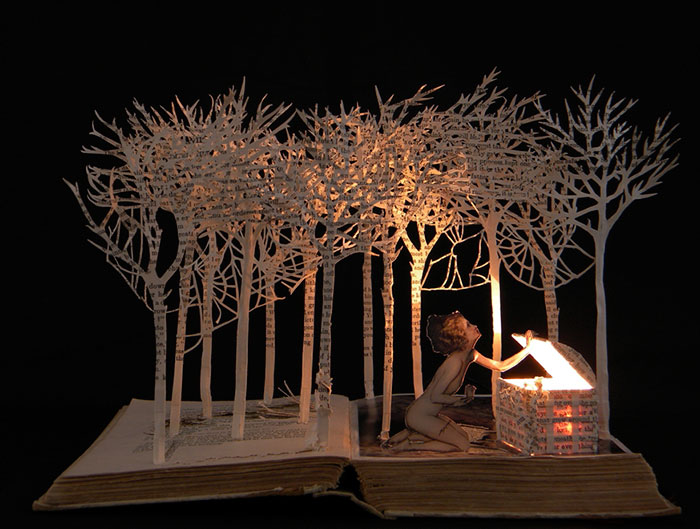

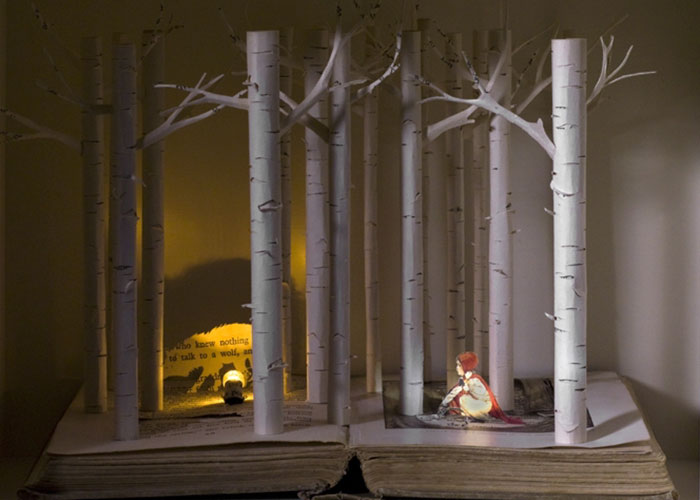

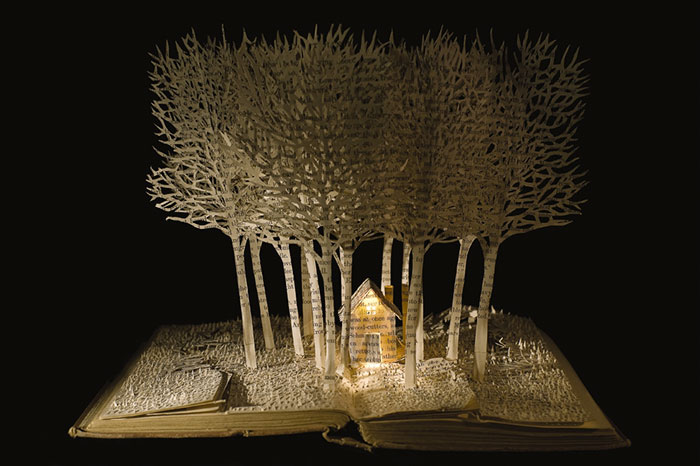

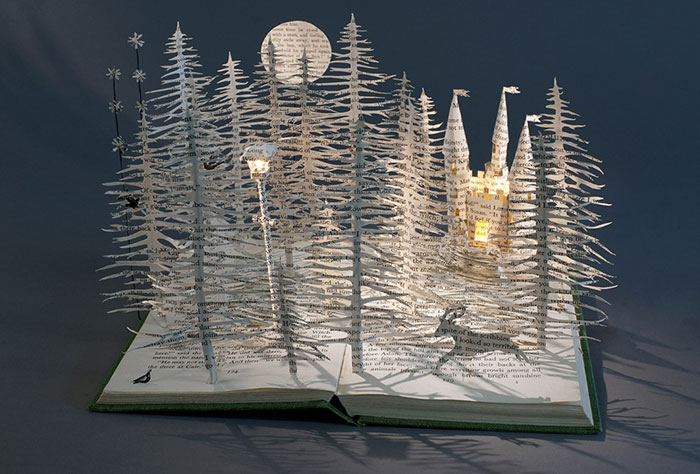

Illustrations by the incredible artist Su Blackwell who turned old books into magical fairytale sculptures.

If you value what I do, you can support me by sharing my articles and poems, buy my books or donate some magic coins in my hat on Paypal. By supporting me, you allow me the freedom and ability to be even more creative and contribute with more. All proceeds go towards expanding my work made of love, including publishing my books, my humanitarian projects and creating content including courses and holistic programs.

Your support means so much to me! Thank you wholeheartedly!